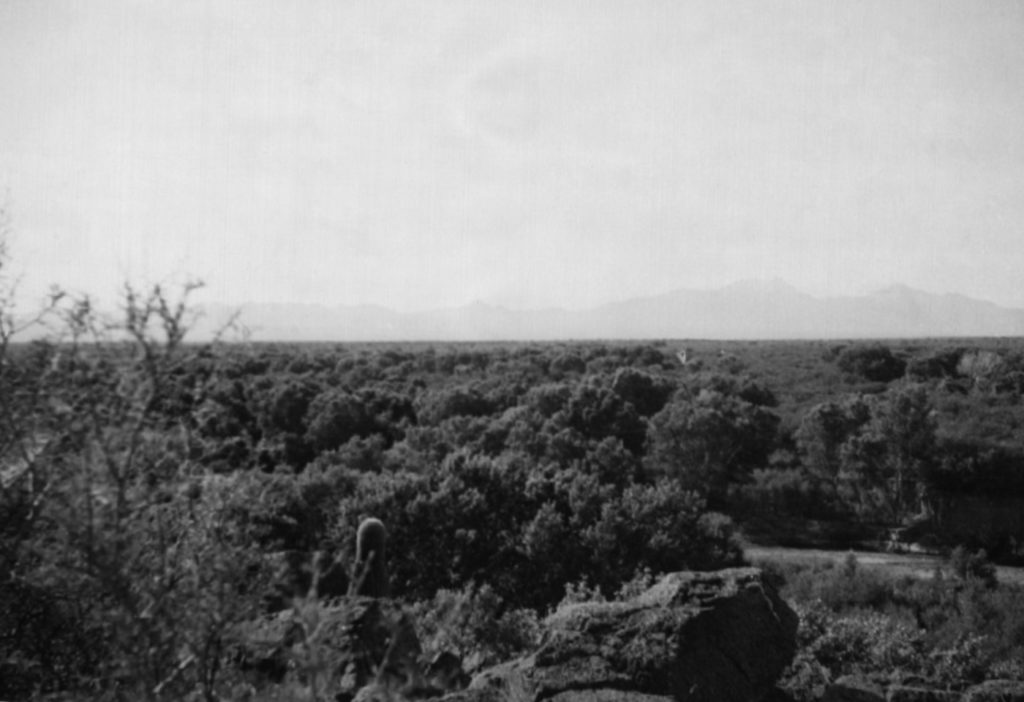

Wa:k Hik dan Riparian Restoration Project on Tohono O’odham land near the San Xavier Mission

By reducing pumping of groundwater in the area, as Colorado River Water imported via the CAP canal is now being used instead of pumped groundwater for many area homes, mines, and farm fields; groundwater levels have risen and resulted in perennial surface flows along this stretch of the river—for the first time in over 70 years.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 5-14-22

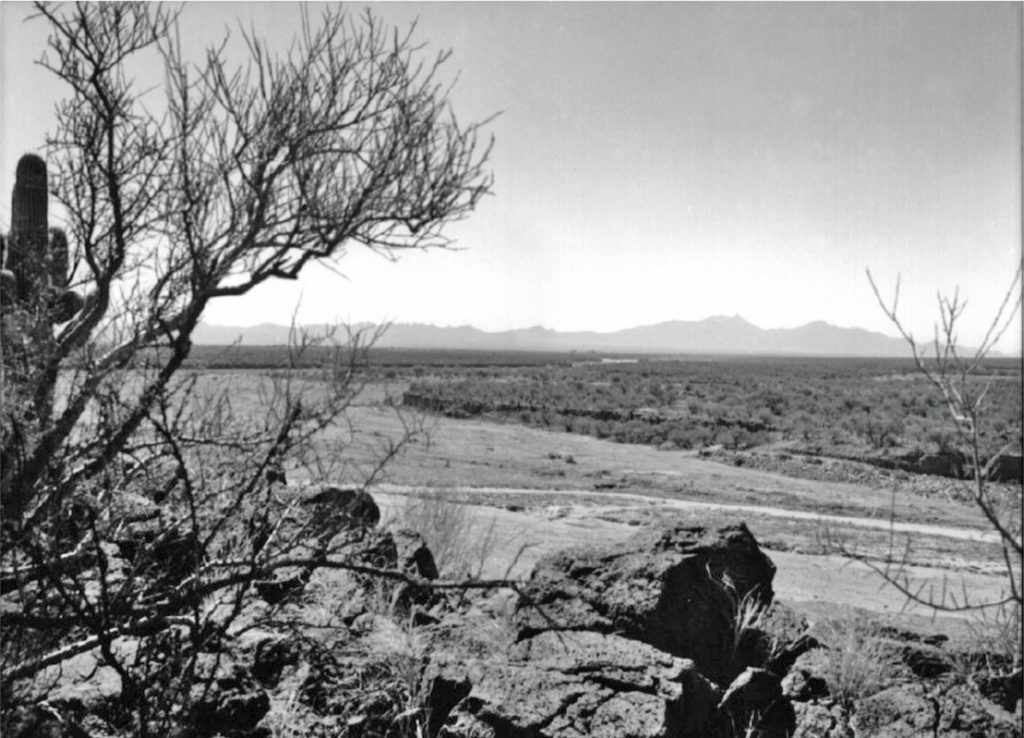

Martinez Hill is where the historic photos (below) of the Great Mesquite Forest were taken.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 5-14-22

How might we similarly recharge more water into our groundwater table than we extract from it without the need to pump/import water from the Colorado River?

How might we better manage our local water resources that are already here?

Traditional ak-chin runoff farming – planting the rain to irrigate crops

The Tohono O’odham have a rich history and traditions of productive runoff farming, sometimes called ak-chin.

A mentor of mine, Clifford Pablo, used to farm this way with his grandfather in San Xavier district fields that were irrigated solely by stormwater runoff directed to the fields. But this came to an end in the 1960s when the construction of I-19 cut off the majority of the stormwater flow.

As an adult, Clifford set up a new runoff-irrigated field with his wife and kids further west in the San Xavier district. The harvested stormwater also provided free fertilizer in the form of nutrient-rich organic matter such as mesquite leaves and rabbit dropping carried within the runoff. No groundwater, imported water, or synthetic fertilizers were needed.

The family planted crops that needed more water, such as traditional O’odham melon and squash, closer

to the water’s inlet and placed drought-tolerant nitrogen-fixing tepary beans farther down the field. In the middle they planted corn and chiles. On the perimeter mesquite trees with sweet, carob-like pods formed a wind- and sun-break along with fencing. Cholla cactus and its edible flower buds also grew there, providing another harvest. Native nitrogen-fixing bean trees added more nutrients, deflected winds, and shaded out some of the intense summer sun.

But Clifford had to abandon this runoff farm when a dam broke at the Asarco copper mine, sending a toxic flow into the farm’s watershed and field. Clifford went on to teach others how to do ak-chin runoff farming in other areas, but we all would be better off if these productive traditional runoff fields and their watersheds were valued and preserved, rather than disrupted and destroyed.

The Great Mesquite Forest

This area, and further south of Martinez Hill used to be called the Great Mesquite Forest a seven square mile ecological wonderland that attracted ornithologists from around the world. Old growth trees were four feet in diameter and more than 65 feet tall. About seventy-three species of birds nested in this forest. But overpumping of the groundwater beginning in the 1920s led to dropping groundwater levels below the trees roots, which led to the death of the forest.

Photo: USGS

With groundwater rising and surface flow returning to this area, a new Great Mesquite Forest may be able to someday return, though currently the down cut river channel is much lower than the adjoining floodplain where the bulk of the forest grew. Before the channel erosively down cut, flood flows could easily and beneficially spread throughout that historic floodplain and better contribute to the natural recharge of the groundwater.

For more information on the Wa:k Hik dan Riparian Restoration Project see:

The Arizona Daily Star 9-30-2019 article by Tony Davis “The Santa Cruz River starts thriving again, water supply is restored”

The Arizona Republic 4-26-2016 article by Brandon Loomis “Replenishing a dried-up Arizona river a few drops at a time”

For more information on Tohono O’odham runoff farming see:

“The Desert Smells Like Rain: A Naturalist in O’odham Country” by Gary Paul Nabhan

“Killing the Hidden Waters” by Charles Bowden

“At the Desert’s Green Edge: An Ethnobotany of the Gila River Pima” by Amadeo M. Rea

“Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition” by Brad Lancaster. Especially see appendix 2.

For more on the history of the Santa Cruz River and the Great Mesquite Forest see:

“Requiem for the Santa Cruz: An Environmental History of an Arizona River” by Robert H. Webb, Julio L. Betancourt, R. Roy Johnson, and Raymond M. Turner

Contact the San Xavier District of the Tohono O’odham Nation for permission and tours of the restoration site.

Where:

There is a public right-of-way pull out on the left side of the south-bound on-ramp road to I-10 from W San Xavier Road. From here you can look east to the Santa Cruz River bed where it goes under I-10, you will likely see the new surface flow there.

Do NOT cross the barbed wire fence. You must have permission from the Tribe to go any closer.

The area is regularly patrolled.

32.104220, -110.994536

This location is included in the following tours:

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1