Roman- and Byzantine-era Cisterns of the Past Reviving Life in the Present

All photos and text by Brad Lancaster, www.HarvestingRainwater.com © 2011

This is number six in a series of Drops in a Bucket Blog posts on Brad Lancaster’s water wanderings in the Middle East; this trip led in part to Volume 1 of Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond being translated into Arabic, and Brad’s participation in the upcoming International Permaculture Convergence in Jordan this September. NOTE: If traveling to the Middle East, check out this blog series for dynamic projects and sites to check out.

In northern Jordan during the summer of 2009, I was on a mission to document a modern-day Roman-era cistern resurgence. I met with Engineer and Permaculture Project Manager Sameeh Al-Nuimat at the Care International office outside Amman. He was great. He has rural hardworking roots, loves native plants and traditional ways, is very enthusiastic and knowledgeable about whole-system design, and decided we’d begin the day by having an Arabic breakfast with everyone in the office. We all grouped around a very small, low table piled high with hummus, pita, olives, falafel etc, and ate with our hands. What a wonderful way to bring everyone together as the day begins!

The Village of Rainwater Tea

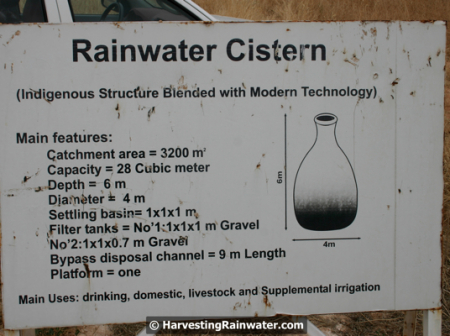

We then made for the water. In the village of Bayudah Al Shrquia there is a long tradition of rainwater harvesting. Roman- and Byzantine-era cisterns abound in both ruin and reuse, with the limestone hills peppered with underground tanks dug into the rock. Many of these tanks have been in continual use since their creation over a thousand years ago, while others have been newly refurbished, funded in part by revolving community loan funds often facilitated by Care International. The cisterns are olla-shaped, and often built below a limestone catchment. A depressed sediment trap just in front of the cistern’s water entrance is usually the only filtration. A boulder with a trap door is put atop the cistern opening so no one falls in.

Villagers covet their rainwater for drinking and cooking, while municipal and trucked-in water is used only for washing and periodic supplemental irrigation. The water truck usually does not come more than once a week — or even just once every three weeks. I saw many systems on this trip and drank lots of sweet rainwater. Many underground tanks simply have a can or bucket on a rope to pull the water up the cistern so it can be carried into the house. Sameeh filled two glasses with cistern water direct from one such can (no complex filtration) and we drank it down — absolutely delicious and revitalizing! For some of the simple, passive filtration used in these domestic systems, see the cistern principles in Chapter 3 of “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1.”

I was also treated to rainwater tea with mint as I interviewed a family about their water-harvesting system. They all loved their system, and had far more trust in their home’s rainwater-harvesting system, which they themselves could manage, than in the intermittent, lower-quality, and less dependable municipal and trucked-in water systems over which they had no control. As they said, “Water you catch you have.”

Sameeh then took me to a new 10,500-gallon (40 m3) cistern being built in the Roman style. The crew of four Egyptian men digging the cistern would lower themselves into the excavation via a rope on a pulley that was supported by a tripod above the hole. I immediately asked if I could go down inside — and did so, to everyone’s entertainment. This was so good! These cisterns are still being built the old way — except for the jackhammer, which now speeds the process along. After excavation, the tank is plastered watertight. This crew builds 35 cisterns a year. In clay soil the excavation takes 8 days; in rock it takes longer. I was thrilled to experience this, and realize that this strategy, this technology never died here, but has continued, and is now expanding again.

Dig a hole, find a cistern.

Next I traveled to other areas of northern Jordan, near Amman (average annual rainfall 10.7 inches or 272 mm — NOTE: such cistern rehabilitation is often not funded in areas that receive less than 7.8 inches or 200 mm annual rainfall) to see similar work by NGOs Mercy Corps and JOHUD. Here new homes are being built at a rapid rate, but there is not the municipal water infrastructure to support them. Instead, rainwater does, thanks to the work of the past.

Ancient cisterns are regularly found when foundations or tree holes are dug for new homes. They are then cleaned out, replastered if necessary, and capped with a concrete ring and steel door. Downspouts from the roof direct rainwater into the tank, and a pump is placed within the tank to direct the water into the home’s plumbing system.

Again, revolving community loan funds (often initiated by Care International, Mercy Corps, or JOHUD) typically fund the restoration of these cisterns. The community decides how to distribute the loans, to whom, for how much, and for what projects. Water harvesting, organic agriculture, women’s empowerment, and composting are typical funded projects — but community empowerment is the ultimate goal, as to receive the grants for loans, the communities must organize, learn to articulate their issues, do accounting, and give everyone equal representation in the decision-making processes.

Mercy Corps alone reports over 1,200 recipients of water-harvesting-project funding in just 2.5 years, with a cumulative total of almost 16 million gallons (60,000 cubic meters) of water harvested. Everyone who receives a system also gets 10 days of training and, after the water tests clean, a key to the cistern. This also helps economically challenged municipalities which currently deliver water at a cost lower than that of treating and transporting it. And it helps the environment because current municipal water and groundwater consumption exceed safe yield, meaning water is being pumped and consumed at a rate exceeding natural recharge. Thus wells and waterways are going dry. The cistern systems do not add to the extraction of dwindling imported/pumped in water.

Harvested rainwater goes further in the communities also implementing greywater-harvesting systems to reuse the rainwater after it has been used for its primary purposes. The rainwater goes further still when those local on-site waters are used to irrigate food that is grown on-site and fertilized with compost (household wastes transformed into another household resource — one that increases the moisture-retaining ability of the soil).

Upping the scale

While these projects were typically at the household scale there is precedent for the community scale. The last stop was the 19th-century Greek Orthodox St. George’s Church in Madaba built atop a 4th century cistern that is so large, and has so many underground channels entering it, that the church now has no clue how large its original watershed was. The watershed seems to include much of the old city — collecting water off the worn cobblestone streets (and the overflow rainwater from the ancient household cistern systems above).

The labyrinth of underground pipes and channels reminded me of the myriad water pipes below all our modern cities and communities. But here in this ancient infrastructure, water was not drained out of the community. Now, however, a whole separate system of pipes imports water at great cost from elsewhere to replace the stormwater that is drained away. Here in northern Jordan the old systems valued and utilized every drop of free, high-quality, local rainwater. For local water was the only water.

And these ancient strategies are needed now more than ever. They were forgotten for awhile, but we are remembering again.

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1