Farming in the City with Runoff From a Street

by Brad Lancaster, Drops in a Bucket Blog, www.HarvestingRainwater.com, © 2008, 2014

The following is one of my favorite water-harvesting stories. It comes from the life experience of one of my mentors, Russ Buhrow, and has inspired me in much of my work. It is amazing what Russ produced with stormwater, something too many people consider to be a waste or a liability. However, as Russ shows, stormwater is actually a great resource.

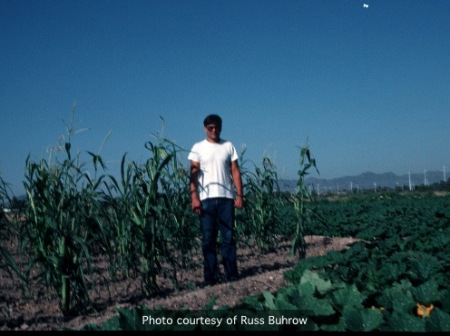

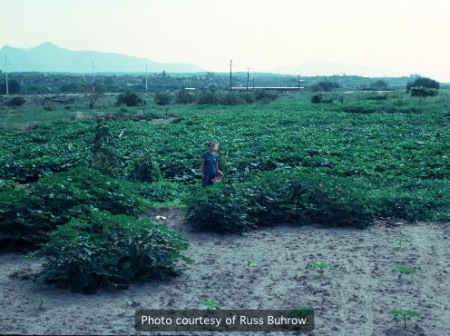

In the summer of 1980, plant-sciences graduate student Russ Buhrow decided to take a break from the books to gain hands-on knowledge through dry-farming in the middle of the simmering desert city of Tucson, Arizona, where annual rainfall averages 11 inches (280 mm). Taking his cue from the ancient traditions of indigenous Tohono O’odham, Russ raised his crops solely on direct rainfall and runoff harvested from short bursts of sporadic summer monsoon rains. Russ’s situation was somewhat different from his Native American neighbors, though. He didn’t farm alluvial flats of a healthy desert ecosystem where runoff from surrounding mountains flows down a braiding arroyo to a field. Instead, he farmed a semi-urban vacant lot between a dry riverbed and cinder-block apartment buildings. Rather than intercepting runoff from low-desert mountains and foothills, Russ learned to harvest runoff from rooftops, yards, parking lots, and a city street.

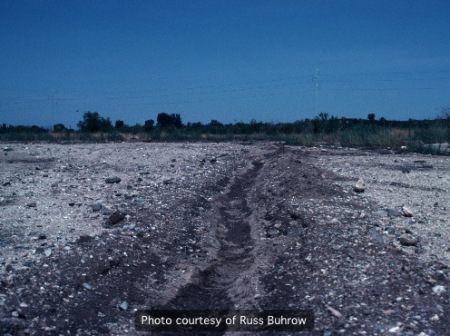

Russ began by observing the gradually sloping, arable vacant lot. Wheel ruts crisscrossed it. Random piles of compacted debris were strewn about, and dense weeds grew in depressions where rainwater and organic matter collected. “Ah ha!” thought Russ. “The weeds grow where the water is, so that’s where my garden will go!”

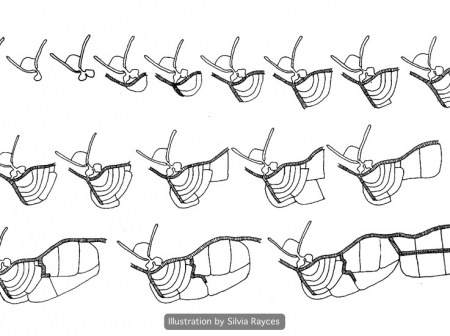

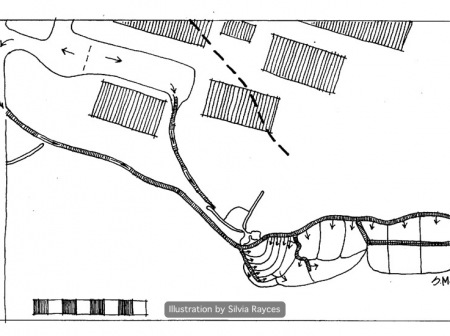

With permission from the landowner, he dug several 8- x 8-foot (2.4- x 2.4-m) sunken garden beds where the weeds grew tallest. Berms stretched to either side on the downslope side of his basins, like open arms for rainwater runoff (see Fig. 1 for the multi-year progression of Russ’ fields, and Figs. 2 & 3 for the context in which these fields were located). Russ planted seeds as the summer storms rolled in. Thunder cracked, lightening flashed, and the rain came down in sheets. He stood in the middle of it all and watched. He saw water pool in the garden basins. He also noticed water pouring off a parking lot just upslope of the basins, and quickly dug a ditch as a diversion swale to direct runoff from parking lot to garden.

After 40 minutes the rain stopped. Planted in soil which had just been saturated, his seeds germinated in just 3–5 days. Russ was full of adrenaline. As he says, “When you see the rain flow like that, it’s a EUREKA moment. You see the water and realize that this really works!” The parking-lot ditch had just increased his water resources five-fold. He went right to work, expanding his planting area to 700 square feet (65 m²).

From then on, no matter how far away he was, Russ always ran to the garden when rain started to fall. “It’s amazing how much water you can catch in neighborhoods,” he says. “You just need to watch the sheet flow when it rains.” Rain and runoff revealed the land’s subtle slopes and depressions. He saw how much water flowed and where. Then he figured out how to catch and use it.

For Russ this was a rush—like playing “flood” in a huge sandbox, with lightening! The unlocked car was always nearby so he could leap in when the lightening struck too close.

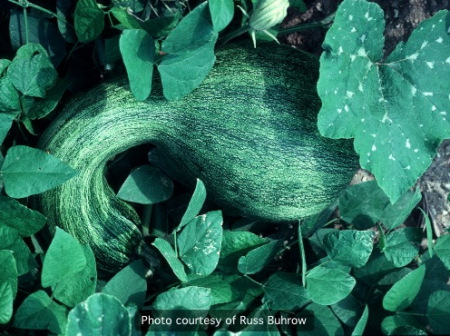

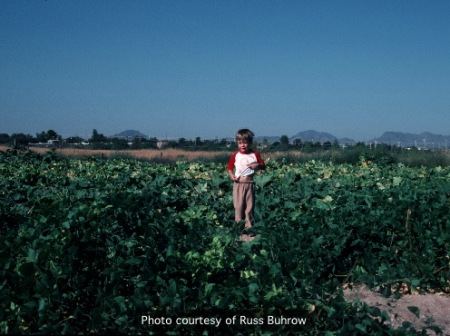

By fall, drought-hardy tepary beans, black-eyed peas, corn, squash, and devil’s claw (a fiber plant with edible seeds and okra-like immature fruit) were harvested—all irrigated only by rain (Figs. 4, 5, 6).

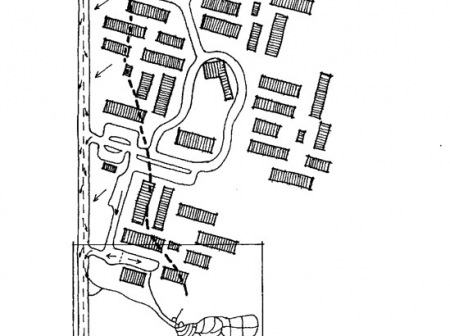

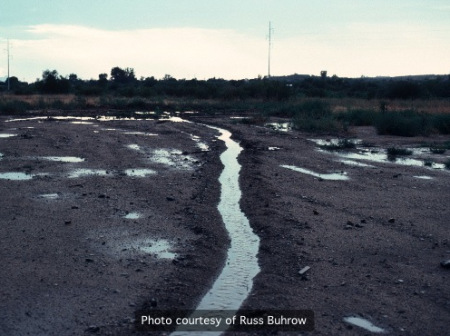

In winter the fields went fallow, but Russ stayed active. Once, standing in the rain, he saw excessive runoff rushing down Columbus Boulevard, an asphalted arterial street that dead-ended 400 yards (366 m) from his garden. “FREE WATER!” Russ yelled. He dug a 1/4-mile (0.4 km) diversion swale/ditch from the street to his garden (Figs. 7A, 7B). He reworked the old garden beds and added new ones. When finished, the garden basins ranged from 100 to 700 square feet (9 to 63 m²) each. Together they resembled a series of stepped terraces that directed overflow water from the upper gardens to the lower gardens (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11). The combined planting area was now 1/2 acre (0.2 ha).

That summer, two big storms flooded the long swale with water 8 inches (20 cm) deep and 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 m) wide. Both storms lasted less than an hour and had Russ running through the garden, euphoric from the water, terrorized by lightening, and exhausted by effort. With the diversion swale running above (upslope of) the top of the terraced garden basins, Russ could temporarily divert the flow into a specific field by cutting an opening in the swale’s berm and then blocking the water’s flow within the swale at a location just downslope of the cut, to force more flow into this field. He created this blockage by throwing wads of weeds and brush into the swale and packing them down with his shovel, his feet, and rocks, then piling dirt behind the brush. Next, he’d run down the swale to the next field, and make a new cut in the berm and a new barrier just downslope of it. Running back up to the first diversion Russ would wait until the first field was well watered, then remove the original barrier of weeds, rock, and soil, and use this material to plug the cut in the berm so the water flowed down the main swale again. That done, he’d run down the swale to make sure the second cut and barrier were diverting water into his second field. If all was well, he’d dash off to the next field for another diversion cut and barrier. And so on, until the water stopped flowing.

Russ estimates he was harvesting as much as 2–3 acre-feet of runoff water a year. That’s 651,700–977,500 gallons (2,467,000–3,700,000 liters). “You had to be there when it rained, and haul ass!” Russ explains. “All could be over within 30 minutes of the first raindrop.”

Russ was passionate about harvesting water, but he made sure he didn’t collect more than could infiltrate into the soil, since if water sits on the soil’s surface for more than two or three days, it can activate a denitrifying bacteria (caused by a lack of oxygen in the soil), which can decrease soil fertility. Yellow spots in fields where water ponds for several days indicate denitrification. Russ prevented such problems by spreading water throughout the landscape, improving the soil’s water-absorbing capacity with organic matter and vegetation, and having adequate spillways for overflow water.

As surplus water overflowed from his fields and moistened the soil beyond and below his gardens, Russ expanded his garden by constructing new sets of terraced fields, each with raised berms to retain overflow water from the fields above (Fig. 1, above). He soon had a full acre (0.4 ha) cultivated with corn, tepary and lima beans, Mixta and Moschata squash, devil’s claw, watermelon, sunflowers, cow peas, and, in a wet fall and winter, I’itoi onions and artichokes (Figs. 12, 13, 14).

Just two decent summer storms, spaced well apart, were enough to support his crops. Russ planted hardy heirloom seeds of dryland crops in coordination with the first good summer rain (see Notes 1 and 2 below). He harvested runoff from rainfalls as light as 0.1 inch (2.54 mm).

Only once in five years did Russ’ fields fail. The rains just wouldn’t cooperate. They were too light, spaced too close together, or too far apart. But when they did cooperate, the fields were very productive. One year, Russ harvested 2 U.S. tons (1.8 metric tons) of mature squash along with another U.S. ton (0.9 metric tons) of calabacitas (immature squash)—400 lbs (180 kg) of which were picked in just one day. In a good season, harvests of 17,000 devil’s claw—the young fruits of are eaten like okra, and the dried fiber of which is used for traditional basketmaking—were common.

Russ had no money for tractors, pumps, pesticides, or water. But he also had no debts since he took no loans. Thanks to working with natural cycles, his only significant investment was his time. Russ describes those times as some of the happiest of his life.

For ten years Russ farmed within the sprawling city of Tucson, relying solely on runoff from desert rains for water. He did not contribute to groundwater depletion, while providing a lot of fresh produce for his family, friends, and neighbors. He was connected with the natural elements: “If you’re not, you fail,” he says. For Russ, this connection was perhaps the greatest benefit of his work, making him feel rooted, part of the natural flow of wind, rain, and sun. Through daily observation he gained numerous insights into the cycles of the Sonoran Desert.

Russ is rarely concerned about food these days. He knows he can grow it—even in the low desert. “All you need is rain,” he says, “and we have enough.”

Enough, that is, if we recognize and value it.

In 1990 Russ went to the Cape Verde Islands, off West Africa, where he used his experience as a resource for part of a USAID study of the islands’ forms of agriculture and diversity of locally adapted food crops. After 3 months he returned and took a full-time job as grounds curator at Tohono Chul Park, where he has created a number of water-harvesting features—including the Jardin Sin Aguas. Russ gives presentations on water harvesting and has a private consultation and design business.

NOTE 1: SOURCE OF DRYLAND-ADAPTED FOOD CROP SEEDS

Native Seeds/SEARCH, 526 N. Fourth Ave, Tucson, AZ 85705. www.nativeseeds.org.

NOTE 2: SPACING PLANTS TO STRETCH SOIL MOISTURE AND BUFFER WINDS

Russ spaced his plantings according to several factors: how much moisture was in the soil, the ability of the plants to withstand strong winds, and the expected size of plants at maturity. Spring plantings were spaced farther apart than summer plantings, since the plants had to survive on residual soil moisture until the summer monsoons. Plants that were easily blown over or snapped by the wind, such as tepary beans and corn, were planted in clusters to support one another. By using wide spacing that took into account the plants’ size at maturity, Russ had easy access for weeding between plants with his roto-tiller and could avoid the use and expense of herbicides.

- Tepary beans were planted in groups of 5 seeds, each group 4 feet (1.2 m) apart.

- Squash seeds were planted in clumps with 3 seeds each, with clumps spaced 8 feet (2.4 m) apart, or just 4 feet (1.2 m) apart if planted late in the growing season, since they wouldn’t get as big before frost hit.

- Devil’s claw seeds were planted in clumps of 3 seeds, each 8 feet (2.4 m) apart.

Plants can be spaced closer if soil is deeper and can infiltrate more water. A silt/loam is good for this, while sand is often too porous. Heavy to medium clay soils can work, but watch the percolation rate. Most roots and nutrients will be in the top 2–4 feet (0.6–1.2 m) of the soil.

NOTE 3: HOW MUCH RAINFALL PRODUCED HOW MUCH PRODUCE?

In 1981, Russ planted seeds at the end of March after the danger of frosts had passed. He germinated the seeds on residual soil moisture from February storms that dropped 1.02 inches (25.9 mm) of rain, and another 2.1 inches (53 mm) of rain in March. The plants got an additional 3.6 inches (91 mm) in April, and 0.45 inches (11.4 mm) in May. Although this was a wet year for the desert, the plants had to survive without any more water for over a month and a half. In July the rains started again, with 2.71 inches (68.8 mm) falling that month, 0.26 inches in August (6.6 mm), 0.47 inches in September (11.9 mm), and no rain in October. On that rainfall alone, the garden produced 9 U.S. tons (8.2 metric tons) of Mixta squash per acre and 26,000 devil’s claw, along with corn, watermelon, tepary beans, and sunflowers.

NOTE 4: THE LOSS OF ARABLE LAND

Russ Buhrow’s runoff farm no longer exists. It has since been built over with a new housing development. Houses are being built within the floodplain upon some of the area’s most fertile soils. If we keep building on—and paving over—our best agricultural land, where will we grow our community’s food?

NOTE 5: POTENTIAL CONTAMINANTS IN STREET RUNOFF

I think more research is needed in the area of street-runoff toxins, and where they end up. Russ tells me he experienced no problems on his farm or with his produce grown a 1/4 mile (0.4 km) from the road itself. I too have never had any problems with plant health where plants have been irrigated with street runoff. The plants have thrived. In street-side stormwater-harvesting basins, while I harvest the fruit from the plants irrigated with street runoff, I make sure none of the fruit has come into direct contact with the street runoff. Thus I harvest fruit and legumes from trees (mesquite pods, desert ironwood seeds, olives, pomegranates, etc). I do not grow leafy green or tuber crops in these basins. More info on my experiences can be found in the resources cited below.

NOTE 6: MORE RESOURCES

• Water-Harvesting from Low Standard Rural Roads, by Bill Zydeek.

www.QuiviraCoalition.org

• Street Orchards for Community Security

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1