Rains of Hurricane Odile Captured in West Texas Water-Harvesting Workshops and Beyond

by Brad Lancaster © 2014

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

My dance with the hurricane rains began on my last day in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as I walked along a beautiful acequia that predates the United States (fig. 1). “Officially” established by the Atrisco Land Grant in 1692, the acequia connected New Spain’s water system to the irrigation systems of the Pueblo Indians. This and other acequias have been in continual use ever since. I love walking along these irrigation canals and experiencing their history, as they are beautiful corridors of water; food; shade; people on foot, bicycle, or horseback; and wildlife. Hands down this is the best way to get around town and connect to this place.

Studies from New Mexico State University (such as Acequias of the Southwestern United States: Elements of resilience in a coupled natural and human system) have also revealed that these acequias enhance the flow of the Río Grande River and the quality of associated groundwater—which is the lifeblood of both the community and the State of New Mexico. These unlined canals move the river’s waters throughout the whole of its floodplain, helping to reduce flooding in wet times. For similar reasons, the river is able to flow longer in dry times: Because much of the water that infiltrates the soil along the canals and throughout the floodplain slowly migrates back to the river by seeping through the soil (beneath the surface), evaporative loss of the water is greatly reduced. That slow seeping through the soil recharges the river up to 3 months after the rains and their runoff have ceased. The subsurface seeping also keeps the water cooler, as does the shade from the cottonwood-tree galleries and willows along the river’s banks—all of which is great for improving water quality, flood/erosion control, fish habitat, and soil building.

These are natural living systems/processes we can build on. Such had been the goal of a seven-day Water-Harvesting Certification Course with Watershed Management Group I had just helped teach in Albuquerque. The acequia walk gave me a little rejuvenation time before catching a bus to Ciudad Juárez, México, the location of the next stop on my trip.

Ciudad Juárez, México

I was invited to Juárez by the Border Environment Cooperation Commission (BECC) / Comisión de Cooperación Ecológica Fronteriza (COCEF). The rains arrived before I did and I was met with flooding in many parts of the city (fig. 2). This video illustrates the flooding best.

Juárez is in desperate need of infiltration strategies since, as is the case in any typical urban setting, the majority of the land is paved over, which generates flooding runoff. But conditions are made much worse by the fact that large parts of the city are built within the historic floodplain of the Río Grande River. Now, due to the engineered channelization of the river, many of these areas are below the river. In addition, the sparsely vegetated Sierra de Juárez on the west side of the city drains much of its ample runoff directly into the city’s impervious concrete and asphalt infrastructure. And to top it off, a large part of the city is built on a historic playa, or ephemeral lake. After a number of very dry years, people forgot that the playa fills with water in big storms. They built where no one should—then the rains returned and flood damage was catastrophic.

As there are few opportunities to drain water, there is great potential and need to infiltrate water—especially since this is a dryland city where average annual rainfall is just 12 inches (300 mm) per year. For too long the gift of rain has been rejected, resulting in a built environment that treats the rain as a burden.

This was made painfully obvious when I learned that ancient acequias in Juárez, as old as those in Albuquerque, have recently had their functions reversed, and are now clad in concrete and used to drain water out of parts of the city, instead of increasing the infiltration of Río Grande River water throughout its historic floodplain. Upon hearing this, I immediately began to wonder how these old acequia rights-of-ways could again be turned into unpaved, living infiltration infrastructure—this time infiltrating runoff from city infrastructure rather than the diverted river water they used to accommodate.

As brainstorming and conversation continued, we were whisked off to BECC/COCEF’s conference on green-infrastructure potential on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. I had the honor of being able to present on neighborhood-initiated green-infrastructure/water-harvesting efforts in Tucson (fig. 5). Sam Rose of Raíz de Fondo in La Paz, México, followed up by presenting on Green Infrastructure implemented in La Paz, some of which I had had the pleasure of helping facilitate. Sam also announced the release of a Spanish edition of Green Infrastructure for Southwestern Neighborhoods (Infraestructura Verde para Comunidades del Desierto Sonorense). Then Irene Ogata from the City of Tucson enlightened everyone on how Tucson had shifted policies from discouraging rainwater harvesting to encouraging, incentivizing, and mandating it—an example of what other cities could likewise do! Commentator Mario López from CONAGUA (the National Water Commission of Mexico) then wrapped things up with a great verdict—he felt Green Infrastructure was possible in Mexico and should be pursued! Huge thanks to Ana Cordova of El Colegio de la Frontera Norte who was a big player in making this panel and conference happen. A dozen or more video clips from the conference can be found on the COCEF/BECC YouTube channel.

Unfortunately I was not able to stay for the second day of the conference, as I had to catch a pre-dawn ride to Marfa, Texas, to continue my series of events.

Day One in Marfa and Alpine, Texas

Arriving at 6 am, I met Chris Hillen of Marfa International School and hit the ground running, assessing the site for a workshop I’d teach at the school two days later. A few short hours later, with the gears of preparation set into in motion, I ran down to the Marfa NPR radio station for an interview arranged by my Will Juett, my main host in Alpine. You can listen to the resulting interview here. This was an awesome precursor to the upcoming weekend’s public talks and hands-on workshops, as this station broadcasts its signal throughout west Texas, plus which the station is thriving, and the staff is wonderful (fig. 6). In such a rural area so far from any big cities it is surreal to be able to turn on the radio and find this station.

With lunch eaten, it was off to neighboring Alpine, Texas, for some panic-fueled efforts to get the Alpine Public Library’s site ready for the next day’s hands-on water-harvesting workshop.

When we arrived, Bryce, the backhoe operator from Big Bend Telephone, was already waiting to dig. I hadn’t yet had a chance to walk the site and figure out what we needed him to do, though, so I began rushing around with a laser level, accompanied by site-assistant Jared, trying to make sense of the site’s slopes and how best to harvest its waters. Things were not immediately coming together: The slopes were subtle, our limited time with Bryce and his backhoe was ticking, everyone was looking to me for the plan of action—and I did not have a clue where to begin. My panic level crept upward. What to do?

I decided to share the panic. I calmly told everyone how and why I was internally freaking out, and what I was trying to ascertain. With that aired, I could relax a little more. I then reminded myself that it didn’t really matter if we moved any dirt with the backhoe or a shovel. The most important thing was that we figured out what was currently happening on the site in regards to water and sediment flow. If during the workshop we could convey how we read and understand the site’s dynamics, everything would be fine, as reading patterns is the first step and what design should be informed by and built upon. Pattern-reading is the foundational work.

Grounding myself by simply reading and observing the land was my salvation. We tracked the current water flow with the laser level—water of course flows downhill—and via the density and vigor of the weeds and Bermuda grass growing along the water’s flow path. It became clear that runoff from the east side of the library’s roof, along with all its parking-lot water, drained through the northeast corner of the parking lot, away from the site’s recent tree plantings, and straight into the street to the north—huge loss of potential (fig. 8).

We then marked out a contour line with landscape flags just below where the water drained off the parking lot. This was the highest point where we could begin, and thus have the greatest potential to use existing elevations to distribute water with the free power of gravity. It also follows the water-harvesting principle of “starting at the top.”

Contour marked, we checked the elevation of the land beyond it. Things started to look promising! It looked like we could back the incoming water up and spread it out over a much wider area behind a contour/diversion berm along the contour line we had just marked (fig. 10), and then direct the overflow water over a very subtle ridgeline (which up to this point had ensured that all the runoff water wastefully went to the street). By crossing that ridgeline, we could divert the runoff water to a wide natural basin that up until now had never received any beneficial runoff inputs from the site’s abundant roof and pavement—thereby allowing for a huge gain of potential.

Cool! Things were starting to make sense. And best of all, we were not driving the design—the site was! The next set of questions was where would the overflow water from the basin go, and how would it get there? (Remember that you always need an overflow route, and you strive to enhance the potential of that overflow. This is one of the Eight Water Harvesting Principles thoroughly covered in my books, a principle which I always run through my head when a plan starts to form.) We continued taking more elevation measurements with the laser level.

I had in my mind that we’d put in a subtle, wide, and shallow diversion channel that would meander the overflow water over more area before it finally spilled over into the street. That approach was a problem, though, as I was coming at this with a preconceived idea of a strategy that I wanted to use. Thankfully I caught myself. “Drop the strategy, Brad,” I ordered myself, “and just read the pattern on the land.”

Into focus came the realization that, due to the site’s subtle slope and the shallowness of the natural basin, a diversion channel would be an anti-water-harvesting strategy. Since the elevation of the diversion channel’s bottom would be the same as the elevation of the bottom of the shallow natural basin, it would thus drain the water we wanted to harvest and infiltrate within the basin.

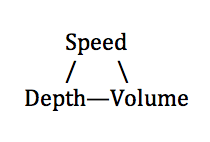

Channeling water flow is also problematic in that it can increase all three points of the erosion triangle:

Increase any one of the three with flowing water, and you increase the water’s ability to pick up and carry sediment, potentially leading to erosion. (See appendix 1 of Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition, for more on this triangle and how your understanding of these processes can shift your designs to work with, rather than against, natural systems.)

Increase any one of the three with flowing water, and you increase the water’s ability to pick up and carry sediment, potentially leading to erosion. (See appendix 1 of Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition, for more on this triangle and how your understanding of these processes can shift your designs to work with, rather than against, natural systems.)

We kept taking levels to ascertain how deep the basin was in relation to the elevation of potential overflow points—the greater the difference between these two points, the greater the water-storage/harvesting potential of your basin. (See the Three Key Elevation Relationships on page 50 in Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2.)

We then noticed that the downslope edge of the natural basin was almost perfectly level. OH YEAH! We did not need any overflow channel at all! Instead we could simply allow the water to fill naturally to the top of the basin’s downstream edge, at which point overflow water would spill over a very wide (40+-foot) swath of fairly level land as a slow-moving, shallow, low-volume sheet flow of water. This is way better than a relatively narrow overflow channel that would increase the potentially erosive speed, depth, and volume of the flowing water.

This also meant less work. The plan I had drawn up before the trip (fig. 9), informed by a satellite image of the site on Google Maps and phenomenal workshop-organizer Will Juett’s observations of the site in a light rain, would have led to a lot of earth-moving. But when I got myself onto the land where I could read and interpret its subtleties, I was better able to work with what already existed, dramatically reducing the work load and expense of the project.

This was a huge relief! We got Bryce working on the contour/diversion berm below the parking lot’s water outlet (fig. 10). We marked out some basins on the upslope side of the berm for him to dig out to generate the soil we would need for the berm (though in hindsight another option would have been to dig out the needed soil from the natural basin). Then Will and I double- and triple- checked all the elevation relationships to make sure all would work as we were imagining.

We got to this point none too soon, as by then it was time to squeeze in a quick meal to balance out my blood-sugar crash—HUGE thanks to long-time Texas water-harvesting advocates Jane Henry and Gwynne Juett who made sure I always ate well, and was thus able to keep up the insane pace of this trip—before giving my Alpine public talk at the historic Granada Theater (while Bryce expertly wrapped up the backhoe work). I took a quick sink-bath in the restroom, changed my sweat-soaked shirt for clean one, and delivered my talk to an audience of over 100 people. It went great—after which Stephen Wood, the owner of the Granada, treated the organizers and me each to a Texas-sized “shot” (a nearly full glass) of tequila and a fine beer chaser!

Day Two in Alpine and Marfa, Texas

I was up before dawn the next day for final workshop preparations and to check the weather forecast. I didn’t realize it then, but we were soon to get the greatest blessing you could ever get in my field of work.

We had a great turnout for the workshop with lots of hard-working, thoughtful participants. They all did a great job, and just as we finished, the raindrops began to fall, and they kept falling! We got a huge downpour and with it, immediate on-site feedback on how our systems worked—in short, wonderfully (figs. 11–17)!

^Figure 13. Movie of how water spread and flowed through site immediately after the workshop. Note that where water flows off the parking lot, we purposely made a drop-off waterfall so that water and sediment would speed up—preventing detritus berms from forming at the diversion berm’s inlet point. Also note how much water we spread and backed up around the trees on the site. Before the workshop none of this water would’ve reached these trees. Instead the water would’ve all wastefully drained straight to the street.

Workshop and celebratory dancing-in-the-rain over, we then went to look at an amazing rain garden Will Juett is creating at the Alpine office of the USDA. Its water-harvesting capacity will be huge, harvesting both roof runoff in tanks and street runoff in the soil. Furthermore, Will is featuring the perennial vegetation of many of the different regional ecotones. This will be a fantastic educational site once complete. I also have to thank Will for all the incredible organizing and fundraising he did to enable me to teach and present in West Texas, while offering everything to the public for free! (Will was able to accomplish this through his own resourcefulness AND the generous support of the Highland Soil and Water Conservation District, Big Bend Soil and Water Conservation District, Texas Master Naturalists Tierra Grande Chapter, Dixon Water Foundation, and Big Bend Telephone. Paige Delaney, the Executive Director of the Alpine Public Library, was also extremely supportive in making the library workshop possible—plus which she kept workshop participants in snacks! THANK YOU TO ALL!)

But the pace of the weekend was not about to slow down, so we headed back to Marfa for my evening presentation at the beautiful Crowley Theater—with another great showing of people.

After the presentation, we went to the Museum of Electronic Wonders and Late Night Grilled Cheese Parlour (fig. 18) for food, then crossed the street to the Planet Marfa beer garden for local beer, conversation, and great music by Chris Hillen and Austin band the Ugly Beats. A perfect end to a nonstop day—and I even met up with a number of fellow Tucsonans!

Day Three in Marfa

Sunday brought the second hands-on water-harvesting workshop of the weekend—this time at the Marfa International School. This workshop’s crew was likewise made up of great people doing great work. But this time the rains came before we were able finish up—which was no problem as this enabled us to see exactly how the water and sediment now flowed on site, and led to a great discussion on how those flows could be worked with in future workshops/work parties.

As the rain ceased around the time the workshop was scheduled to end, most of the crew headed home. Superheroes Joselyn, Terry, and Don stayed on to help me wrap up the loose ends from the workshop. It was pitch black by the time we finished at 9:30 pm, but we got it done… well, almost. We had accomplished the first phase—planting the rainwater with a series of stepped basins—but we left the next step of planting the trees in the basins for the school’s students and their parents. This was headmaster David Sudderth’s brilliant idea, for he knew the planting of those trees would be a means of enabling the community to literally root themselves—along with the trees—into the soil and future of the school.

Big Bend National Park

I spent my last day in the Trans Pecos region exploring Big Bend National Park. I hiked down Dog Canyon to find delicious native Texas Persimmons (fig. 19) and then up the Lost Mine Trail for the view from the rim (fig. 20) and on to a hidden waterfall (fig. 21). After finishing this last stretch, I had just enough time to get to the Río Grande River before sunset. I had started my trip along the Río Grande River in Albuquerque, followed it to Ciudad Juárez, and was now ending it along the river on the Texas-México border—perfect!

All along the way I was collaborating with others throughout the Río Grande River watershed who are likewise striving to plant the gift of the rain in a way that enhances the potential of our communities and the living systems upon which we all depend. I’m so grateful for the opportunity to do so with this growing community of wonderful, aware people. Hope was renewed. And I returned to Tucson via the Amtrak observational car, loving the opportunity to drink in the beautiful wide-open vistas along the way.

Postscripts

Postscript 1: Along with all my great hosts, I’ve got to thank my assistant Megan Hartman who expertly coordinated with everyone to help pull off this this tightly-packed trip.

Postscript 2: One of the biggest challenges with these out-of-town hands-on workshops is dropping in to places for the very first time, with a very small window of time, and needing to assess the site and then generate a plan of action within a few hours. I’m looked upon as the outside (ex) expert, but the true measure of success of the systems created in the workshops is how engaged the local (in) experts—or rather inperts—are (credit for this term, inpert, goes to David Eisenberg). The more time we can spend on a site to observe its patterns, the more successfully we can work with them. The local inperts are perfectly situated for that. Even with systems implemented, they can be continually reassessed in wet and dry times—then tweaked or altered as needed. Nothing is meant to be fixed or permanent—rather all must continue to evolve as our understandings and relationships with the natural patterns likewise evolve.

My books, presentations, and teachings strive to enhance our awareness of these relationships—to subsequently enhance the evolutions of our understanding and conscious actions based on those understandings. As to how far our evolutions go, well, that is up to each and every one of us.

But evolution requires us to start—and we can start as small and simply as getting out in the rain to observe what happens, how things flow, how they grow. Then you might plant a little rain in a way that builds on what is already working.

To see how I dealt with the rains of Hurricane Odile at home in Tucson, see my blog post, Harvesting Rain From a 1,000+-Year Storm Event.

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1