Foreword by Andy Lipkis to Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition

Superheroes are what happens when any among us link hands, say we care, and take smart, effective action.

G’day! How yur tanks?” This four-word greeting changed my life. Twenty-one years ago while traveling up the east coast of Australia with my wife and infant daughter, I noticed that nearly every conversation between rural Australians began with this question.

Instead of the automatic, “How are you?” or “Nice weather,” it was a specific question that— once I figured out what it meant—spoke volumes about these people’s connections: to the land, to each other, and to the environment.

Tanks, also known as cisterns, are the very large containers that store captured rainwater and provide rural Australians with their life support: vital water for drinking, bathing, and gardening. Many rely exclusively on captured rainwater for all their needs.

This one question bundled and abbreviated a collection of concerns: How is your water supply holding out? How has the rain treated you? How are you doing in managing your land and water? How is your family holding up? At what state of readiness do we need to be for our community today?

Having spent much of my life working to awaken people’s awareness and inspire them to take personal responsibility for the environment, I was thunder-struck at the advanced state of consciousness being expressed by these Aussies, and I saw in that awareness an answer to the water crisis facing cities in my native Los Angeles, as well as in arid and non-arid lands around the world.

And for that same reason, I congratulate and thank you for picking up this book. You wouldn’t be reading this if you didn’t have an awareness of the need to take responsibility and action either to secure your own water supply or help solve the larger looming problems. Whether you are in it for selfish or self-less reasons, you are a pioneer and taking on the role of environmental healer. You are an early adapter to a world that is already experiencing ever-increasing water and energy issues because of climate change and other issues.

Your experience, persistence, and success in this new wave of rainwater harvesting may lead the way to wide-scale systemic adoption and implementation in cities around the world.

Rainwater capture is transitioning from an individual act of personal survival and self-reliance, to one that is replanting seeds of community, interdependence, resilience, and sustainability.

The local and global world water situation is becoming urgent. As humans in first-world nations, our consumption and waste of natural resources is generating sufficient pollution and depletion to damage and impair the healthy functioning of nearly every natural system on earth. These ecosystems are our life-support infrastructure for clean, abundant, and safe water, as well as food, oxygen, and a stable climate.

Reversing the degradation requires a profound transformation of individual and communal perspective and behavior.

Instead of believing that government and centralized systems are in charge of the environment, we must shift to the other end of the spectrum where individuals, families, households, neighborhoods, villages, and towns take personal and collective responsibility for repairing and maintaining the ecosystem and its natural life-support systems, with government providing guidance and support.

As you read this book, you’ll find that rainwater harvesting practiced as prescribed herein is really watershed and ecosystem stewardship. In sculpting your landscape and creating water-capture systems, you will be restoring, revitalizing, or mimicking natural systems such as forest watersheds. As such, you’ll be repairing the ecosystem and laying the foundations of your community’s sustainability. And you will be a leader. Any change you make on your home can become a demonstration and model that others—your neighbors, elected officials, and government agency staff—will be able to study, copy, and evolve.

As president of TreePeople, a nonprofit organization I founded 37 years ago, I like to say that we are helping nature heal our cities. Our work is to inspire people to take personal responsibility and participate in making their cities sustainable urban environments. Our prime focus is to support people in designing, planting, and caring for functioning community forests in every neighborhood in Los Angeles (at the time of this writing, one of the world’s least sustainable megacities).

Forests are natural sustainability infrastructures. Trees are the basic earthworks. Trees and forests, and the highly porous and mulched soil beneath them, capture, slow, filter, store, and recycle rainwater, and thereby recharge streams, groundwater aquifers, and springs. They provide protection from droughts, floods, and pollution—cleaning the water so it’s drinkable and usable. Trees and forests sustain life. Unfortunately, when most cities were created, the land’s original watershed functionality was unwittingly destroyed. The idea behind functioning community forests is to plant trees and manage the land in cities in a way that mimics natural forests, bringing water, protection, and resources back to urban residents. However, since urbanization has sealed so much of the land with buildings, roads, and parking lots, simply planting trees and creating green spaces often isn’t enough to make up for the lost watershed. By adding water-harvesting technologies that are designed to mimic nature, such as earthworks (rain gardens, swales, sheet flow spreaders, and others) that are integrated with cisterns, on-site gravity-fed greywater systems, and clearwater recycling/reuse systems, it is possible to replace the watershed and ecosystem functions that were lost.

The magnitude of the water crisis—and the opportunity—became clear to me in 1992, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed to spend half a billion dollars to increase the capacity of the Los Angeles River by raising the height of concrete walls along its banks. The Corps determined that the Los Angeles area had been so overpaved that, instead of soaking into the ground, rainwater from a 100-year storm event would rush off the paved and sealed surfaces so quickly that it would overwhelm the river and flood the nearby cities of southern L.A. County.

It was at that moment that the “How Yur Tanks?” lessons clicked for me. I wondered how much of our 14.7 inches (373 mm) of average annual rainfall we were throwing away each year, and whether we could use that half-billion dollars for cisterns to capture and use that precious rainwater, just like the Australians do. I asked the county’s flood control engineers and they dismissed the idea, stating that replacing the river walls would require installing a 20,000-gallon (75,700-liter) tank at each of one million homes—an expensive and impossible task. The local water supply and stormwater quality agencies had similar responses to my questions. The idea was too expensive for their individual missions and budgets and would require what they considered to be completely unacceptable lifestyle changes on the part of the public. In the process of these discussions, however, I learned that our average rainfall, if harvested and used appropriately, could replace the portion of our imported water that we use for landscape irrigation—roughly half of the one billion dollars’ worth of water the city of Los Angeles IMPORTED every year.

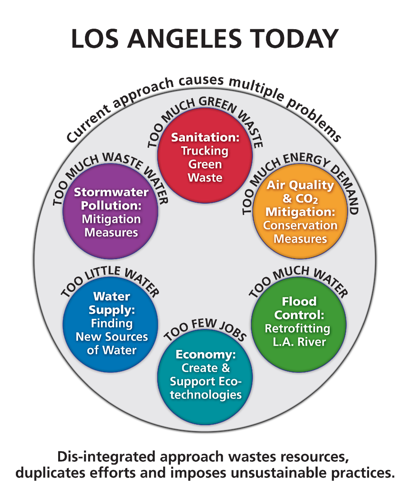

What seemed impossible to the agencies was perfectly logical to me. I researched and found out that the separate water-related agencies had separate, unconnected plans to spend a combined $20 billion in the next decade or so to upgrade or repair their respective systems, yielding only “band-aids” with no overall improvement in sustainability of the region.

So, I began designing a 20,000-gallon (75,700- liter) cistern that could safely fit in a small urban yard without compromising anyone’s lifestyle or posing any threat during our occasional earthquakes. It turned out to be a modular 2-foot-wide, linear, recycled food-grade plastic tank that could replace the fence or wall that separates most urban and suburban residential properties—with overflow directed to a water-harvesting landscape. Further, I proposed to outfit all the tanks with wireless remote-controlled valves and pumps that would enable flood-control, water-supply, and stormwater-quality officials to centrally manage the multitude of independent tanks as one highly adaptable storage network.

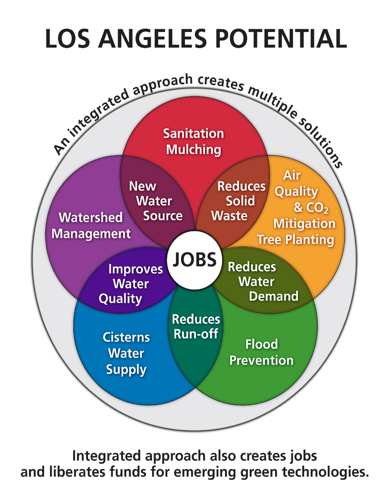

The networked mini-reservoirs of tanks and earthworks could thereby perform at least triple service for potentially less money than all the agencies’ separate projects. By also adapting all the areas’ landscapes to become functioning community forest watersheds, my system was intended to produce multiple additional benefits such as creating tens of thousands of new green-collar jobs, saving copious amounts of electricity (by reducing air-conditioning needs with well-placed shade trees AND reducing the pumping required to import water over the mountains into Los Angeles), reusing all garden and landscape biomass and prunings on site as mulch, creating a new local plastic recycling industry product and market, and creating a disaster-resilient backup local water supply.

This was a lovely and compelling vision, but no one in an official capacity took it seriously. I realized I’d need to do something to prove that the idea was feasible, both technically and economically. That notion turned into a six-year program of design, feasibility, and cost-benefit analysis that became known as the T.R.E.E.S. Project (Transagency Resources for Environmental and Economic Sustainability). It involved hundreds of engineers, landscape and building architects, foresters, scientists, and economists who collaborated to create a book full of designs and specifications (Second Nature, TreePeople, 2000) to retrofit or adapt every major land use in Los Angeles to function as urban forest watersheds. Other team members spent two years conducting a rigorous cost-benefit analysis. And finally, we built a demonstration project, adapting a single-family home in South Los Angeles.

The demonstration site, known as the Hall House (named for its owner, Rozella Hall), had a relatively simple set of interconnected earthworks designed to capture, clean, store, and use rainwater from a massive storm event, and prevent any of the rainwater or biomass from leaving the property and thus being wasted. We built berms around the lawns, installed a mulched swale, put in a diversion drain to pick up driveway runoff and carry it to a sand filter under the lawn, fabricated and installed two modular 1,800-gallon (6,800-liter) fence-cisterns which were fed by roof-top rain gutters through a filter, then connected to the irrigation system, and finally, planted a trellis “green wall” of climbing roses to shade and cool the house’s sun-heated south-facing wall. We also removed 30% of the lawn and replaced the remaining turf area with drought-tolerant grass.

Then, on a hot August day in 1998, we invited our agency partners, numerous public-works officials, and the news media to see the demonstration house. We handed them umbrellas and unleashed a 1,500- year flood event via a fire truck, pumping and spraying on that one house 4,000 gallons (15,100 liters) of water in ten minutes. Officials huddled in stunned silence as they watched the water fall and flow, pooling in the bermed lawns and cistern. They saw that none of the water flowed to the street and storm-drain system. They saw how, in that one instant, their annual billion-dollar burdens of separate infrastructure systems and needs were elegantly bundled and handled. The result: no stormwater pollution, no street flooding, no green waste, dramatic water and energy savings, more attractive landscape, and potentially thousands of new jobs.

The head of L.A. County Public Works’ flood control division couldn’t contain his enthusiasm and proclaimed that the simple elegance meant this demonstration could be easily replicated. A day later, after he and his staff reviewed both our engineered designs and cost-benefit analysis, he called me: “I’m sorry. We didn’t understand. We think you’ve cracked it. Your idea needs to be deployed throughout the whole county, but it’s going to cost more and take more time than you think. But despite that, we need to begin scaling this up immediately. We’d like to try this idea to solve one of the county’s most persistent urban flooding problems.”

That was the beginning of the Sun Valley Watershed project, located in the City of Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley. After a successful two-year feasibility study, the County Public Works Department launched a thorough “stakeholder-led” watershed- management-planning and environmental-impact analysis. Six years later, both the plan and environmental report were approved; construction of the first project began within a few weeks. The plan calls for the retrofit of 20% to 40% of the watershed’s 8,000 homes and their landscapes, and installation of a diverse network of earthworks. The earthworks mix ranges from simple to complex, beginning with tree planting, pavement removal, mulching, and berming. On the more complex end, the projects include installing street swales, and school watershed parks that replace asphalt play yards with permeable green- spaces above large underground infiltration systems and cisterns.

The Sun Valley Watershed planning process informed and transformed many of the participating agencies and organizations and inspired others who followed the process. For example, Los Angeles County Public Works formed a new, integrated Watershed Management Division. The City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation launched and completed its first ever Integrated Resources Plan for Water. And among several cities outside the Los Angeles area, the City of Seattle initiated its Salmon Friendly Seattle program, which seeks to restore viable salmon habitat throughout the metropolitan area by revitalizing watershed and forest functionality in all the city’s neighborhoods.

There are several keys to the projects’ successes so far:

1) we demonstrated that these adaptations represented acceptable and attractive lifestyle changes that would be politically palatable;

2) we demonstrated with rigorous engineering that they were technically feasible, safe, and capable of solving pressing problems;

3) we demonstrated that they were economically feasible by identifying multiple outcomes and benefits that altogether would over time save money for the assembled funding partners; and

4) we engaged and educated all the stakeholders from both the community (including children) and relevant agencies.

This story is far from over. As it continues to unfold it presents a variety of political, jurisdictional, and regulatory issues and problems that we work to resolve. My initial vision was that so much water and money could be saved by local governments that agencies would help individuals and businesses cover the costs of installing and maintaining the systems on their properties. That is now happening in some cities, such as Santa Monica, Seattle, and Houston, which are giving grants for cisterns and water-saving landscapes.

As we confront growing water-quality and supply issues, plus the increased threat of flooding and weather-related calamities, it is increasingly urgent that we find ways of adapting our homes, neighborhoods, towns, and cities to become resilient to climate change and disasters. You have a huge role to play in protecting your household and region by personally implementing some of the water-harvesting practices detailed in this book. If you do this, and make yours a demonstration project, you will help prove that it is feasible and attractive for your region. You will make it more politically palatable, so your local politicians can pass laws, change ordinances and codes, and make resources available to help others implement on a wide scale. And then, collectively, we just might tip the balance and put our nation on the road to a healthy, just, and sustainable future.

Dig in and have fun.

—Andy Lipkis, 2008 Andy Lipkis is Founder and President of TreePeople, a Los Angeles-based social-profit organization that he founded in 1973. Andy collaborates with leaders, cities, businesses, and agencies to identify and implement natural- systems-based solutions to human, social, and infrastructure problems. He co-wrote, with his wife and partner Kate, The Simple Act of Planting A Tree: A Citizen Foresters’ Guide to Healing Your Neighborhood, Your City and Your World, and has been recognized and honored as one of the founders of the Citizen Forestry movement.

Update, 2019

A lot has happened in the past 11 years that both underscores the urgency of taking action to become climate resilient, and validates the viability and scalability of the solutions in this book. These solutions are among the most immediately accessible and powerful paths to making our homes and communities safe, healthy, fun, inspiring and sustainable.

The growing intensity of severe and extreme climate events appear to be mimicking early stages of the cascading ecosystem and civil society declines that led to the disappearance of a number of past civilizations, as documented by Jared Diamond in his book Collapse. Diamond asserts that every civilization throughout human history that forgot its forests, and cut them down without replacing them, triggered loss of soil, local water, food, and a cascading decline of ecosystem and human life-support services, and ultimately disappeared. In contrast, every civilization that noticed the decline and acted to re-establish the trees and protect them, re-established its water, soil, food, and protection from severe weather and social breakdown…and saved themselves. It is not too late. Despite the overwhelming magnitude of these problems, there are actions we can take as individuals and communities to both combat the causes, and adapt our homes, neighborhoods, and cities, to make them much more resilient to these threats.

We urgently need to capture the rain when it falls, to re-hydrate the soil and re-enliven it with more vegetation, microorganisms, and other life. Hydrated, enlivened soils sequester carbon, recharge aquifers, and rebuild the atmospheric short-water cycle, which some hydrologists and climatologists believe will moderate severity and help mitigate the problem.

In California, our demonstration projects, along with others, did indeed build political support, resulting in new laws, programs, and funds which slowly but steadily are enabling the wide-spread scaling of these ideas. LA city’s Department of Water and Power created a Stormwater Capture Master Plan identifying rainwater capture as a source for 45% or more of its local needs. LA area agencies then collaborated with TreePeople to co-design and build a pilot demonstration project wherein 6 homes were retrofitted with rainwater harvesting landscapes, and equipped with remote-controlled and jointly monitored and managed cisterns. That pilot, known as “LA Stormcatcher” showed the benefits of wide-scale adoption. Los Angeles County voters have just approved a property tax to provide $300 million per year to build and maintain rainwater capture and treatment facilities as part of green infrastructure, to both clean up stormwater pollution and increase local water supplies.

During the decade-long “millennium drought” in Australia, numerous changes to water use practices and policies, along with generous financial incentives, resulted in unprecedented numbers of Australians installing residential rainwater cisterns at their urban and suburban homes, (30% of the homes in Sydney and Melbourne, and 50% of the homes in Brisbane and Adelaide), dramatically changing their lifestyles, and cutting water use in half—thus enabling the country to make it through the drought crisis. When the drought ended, most people retained their cisterns, and many added more storage capacity and advanced treatment. Then, in 2009, in the wake of massive, unstoppable, deadly, and devastating wildfires—similar to those in California—new building codes were adopted requiring homes in urban-wildland interface areas to have tanks with at least 5,000 gallons of water on hand for firefighting. This decentralized water supply was needed because the centralized water systems were found to be vulnerable and insufficient to fight the fires.

We need superheroes to quickly stand up and save us. These superheroes are us, our trees, and our shared ecologies! We are it! We have the power to choose and take action immediately. Superheroes aren’t just a few macho strong men and women. Superheroes are what happens when any among us link hands, say we care, and take smart, effective action. That’s community—caring, collaborative, powerful—like the com- munity of life that is a native oak tree.

The minute an acorn (an oak seed) sprouts, before it sends leaves, it puts down a root as far as nine feet (3 m) deep to establish a stable water supply. From there it starts to transform the ecosystem and attract and support all kinds of additional life forms that it relies on to thrive and grow to a 100-foot (30-m) diameter canopy. This massive living organism—one of the largest on the Earth—could not function without the thriving community of earthworms, mycorrhizal fungus, and other tiny critters that live in the soil underneath the tree.

That tree cannot drink unless billions of microscopic fungi hand individual molecules of water to the trees’ roots (for which the tree gives the fungus photosynthesized sugars in thanks). This collaboration might make you ask, “Who’s more powerful in this equation—the largest or the smallest life forms?” But its not about that kind of power—its not about competition. This is a collaborative space where we all need each other. Everything’s happening because life forms are communicating and collaborating.

The oak and its community become a kind of a sponge, with huge capacity to capture water in the massive canopy and the root network of the tree. The rainwater drips slowly through the canopy to the ground below, where the decomposing leaves, mulch, microbes, critters, and animals in the soil capture it and work together to clean and treat it, then they slowly release surplus stormwater in a calm and productive (not flooding and erosive) manner to the watershed and the aquifer. Just one tree and its soil- borne community is a 120,000-gallon (454,000-liter) living cistern, living fire protector, living air conditioner, living flood abatement strategy, and living water treatment facility.

Now is a great time to discover and embrace your inner superhero. You are just like the oak tree community. Plant water and catch water. Plant trees and grow collaboration, fun, and resilient strength with family, friends, and neighbors.

—Andy Lipkis, 2019

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad: