What Renters (and Non-Renters) Can Do to Harvest and Enhance Water, Sun, Shade, Wind, Community, and More

by Brad Lancaster © 2013

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

You don’t need to own property to engage with, harvest, cycle, and enhance your local resources—and your potential to live collaboratively with them. Below are some ideas all elaborated upon within the books Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition and Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2.

General

Deepen your knowledge and experience of the larger living world you live within NOW!

– Get outside into the flows of rain, wind, sun, and shade to observe and experience their characteristics, directions, force, effect, and how they change at different times and seasons. The better you know and understand these natural patterns, the better you can work with them (see chapters 1, 2 and 4, and appendices 1, 7, and 8 in Volume 1).

– Hike in nature to see how life has adapted to local conditions, and how it has evolved to survive and thrive without reliance on outside inputs. Learn about and identify the local plants, wildlife, soils, and geology. Pay attention to how different life forms create and take advantage of unique microclimates, and how you could do likewise.

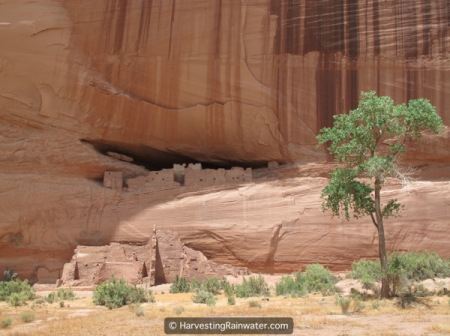

– Seek out and visit sites to see how people are (or were at historic sites) harvesting and enhancing water, sun, shade, wind, and more (figs. 1A & 1B, below). Ask: What works (worked), enhancing the environment? What doesn’t (didn’t)? How could the harvests be done in a more beneficially integrated and regenerative way? How can they inform what you could do?

– Attend related presentations, classes, and workshops. Read books (fig. 2, below). Ask questions.

– Help out and volunteer at sites doing this work, whether such opportunities arise at friends’ or family’s places, schools, houses of worship, parks, neighborhood rights-of-way, or within organizations working to change policy.

– Seek to rent properties already incorporating strategies that harvest water, sun, shade, wind, and more. This way you’ll live and work within such systems, you can more easily directly assess them, and figure out how to improve them further. Inform property owners that you want this, so they realize the market is demanding it. Refer them to Volume 1, www.HarvestingRainwater.com, and other resources if they request more information.

– Advocate for change. As you gain a better understanding of how things could be improved, push for changes in policy that make it easier to do the right thing. For example, in my community of Tucson, AZ, many individual citizens, businesses, and organizations put pressure on governmental organizations (through letters, emails, phone calls, attendance at and participation in public meetings, etc.) to legalize, provide guidance on, then incentivize water- and sun-harvesting strategies. It works!

Rainwater

When it rains, where does the water go? Is it used as a resource or all wastefully drained away? Ponder how simple tweaks of existing systems could improve conditions and effects. This trains your eye and mind to see in new ways, so you learn to identify new potentials.

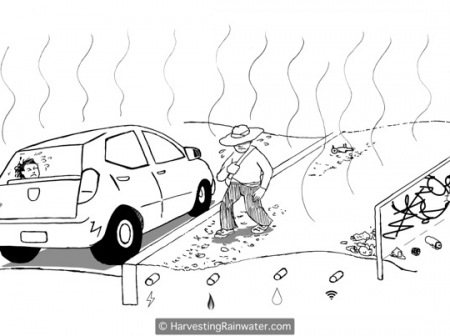

For example, perhaps a water- and soil-draining raised landscape median in a parking lot could be converted to a water- and soil-harvesting sunken landscape median. Better yet, maybe this could be done where parking lot runoff would drain into the sunken landscaped area with a curb cut or curb core. See how a shade tree there could shade and cool the otherwise-exposed pavement and parked cars.

If you have access to a yard:

• Seek permission from the landowner to create a simple, small water-harvesting earthwork or raingarden in a spot where a tree(s) or other vegetation would be beneficial, perhaps out of the way on the periphery of the yard (but where runoff collects) (fig. 3, below). If things go well, inquire about expanding on your successes or trying other strategies. See below for possibilities.

• Build a water- and nutrient-harvesting sponge by leaving a mulch of organic matter (such as fallen leaves) under plants, rather than removing such materials. (Leaves are called “leaves” because we are supposed to leave them where they fall.) If you prune a plant, cut up the prunings and spread them out on the ground below the plant as well (fig. 4, below). Water-harvesting basins do a wonderful job collecting and holding this mulch in place.

With or without access to a yard:

• Start composting to further enhance the sponge, either in a compost bin or by placing your kitchen scraps under the mulch where flies can’t get to them, and where you don’t see or smell them. If you don’t have access to a yard, compost under your sink in a worm bin and offer the worm castings to a neighbor or community garden.

• Consider how you could turn additional on-site “wastes” into resources. If you’re already experienced at composting and inclined to try a compost toilet, in so doing you can safely turn human waste into fully composted humanure. It is best to first try, use, and maintain different systems under the guidance of experienced users. See which system(s) you prefer, since different approaches work for different preferences and site constraints. When ready, see links for guidance on building and using your own site-built bucket system (humanurehandbook.com) or barrel system (www.omick.net/composting_toilets/barrel_toilet.htm)—both of which work great if you have yard space or a well-managed community composting space for the composting process.

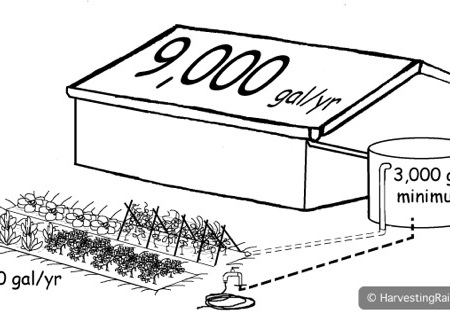

• In terms of harvesting rainwater in a tank, do the calculations in chapter 2 and appendices 3 and 4 of Volume 1 to determine your ideal tank size (based on volume of water coming off your roof, and water needs in landscape and/or home). Then ask yourself: Do you really need a tank to utilize that rainwater? (Passive water-harvesting earthworks or raingardens are typically all you need for associated low-water-use native plantings.) If the need for a tank does exist (perhaps you need to irrigate a high-water-use vegetable garden), consider installing a lightweight, potable-water-grade, polyethylene plastic tank in accordance with the Nine Cistern System Principles in chapter 3 of Volume 1 (fig. 5, below). This way, you can take the tank with you if you move.

Greywater

How much greywater goes down your drains each day or each month? Could you instead reuse that water on site to grow food, shade, wildlife habitat, beauty, and more? See chapters 2 and 5 in Volume 1 and chapter 12 in Volume 2.

– Start using greywater-compatible soaps, body products, and detergents (that won’t hurt your soil, plants, or skin) to see which you like. See Soap & Detergent Info resource of the Greywater Harvesting page at www.HarvestingRainwater.com for tips.

– Put a plastic tub in the rinse basin of your kitchen sink in which you can collect greywater to carry to potted plants or outside plantings (figs. 6, 7A & 7B, below).

– Shower with a bucket at your feet, in which you can capture water running from the faucet until the water gets hot, and much of the shower greywater splashing off your body and head (fig 8A, below). Use that water to flush the toilet by pouring the water into the toilet bowl (not its tank) when you want to flush it (fig. 8B, below). Or carry that water to potted plants or outdoor plantings.

– If you have access to a yard, set up a simple outdoor shower such as a hose over a branch of a tree, under which you can shower in hot summer months. Set up a privacy screening around the shower if needed, or just wear a bathing/swim suit.

– If in a climate where the washing machine can be placed outdoors under a roofed area, direct its greywater to the landscape as described in the greywater chapter of Volume 2. Greywater access from the washing machine is also easy if the washing machine is inside the building, and against an exterior wall. The Laundry to Landscape system from OasisDesign.net or the surge tank and hose systems are both options (figs. 9A, 9B & 9C, below). See Volume 2 for still more options.

Water and Energy Conservation (in addition to strategies above)

Are water-needy plantings situated where free on-site waters (rainwater, roof runoff, greywater, air-conditioning condensate, etc.) naturally collect, or are they in hotter, drier locations where you need to bring water to them? Could things be modified for the better?

How much water is consumed by your energy consumption? How much energy is consumed by your water consumption? How much carbon is emitted by your energy and water consumption? How could you improve upon your current impacts? (See appendix 9 in Volume 1.)

– Install and utilize a low-flow showerhead if there is not already one in place. This also saves hot water and the energy it takes to heat it.

Sun and Shade

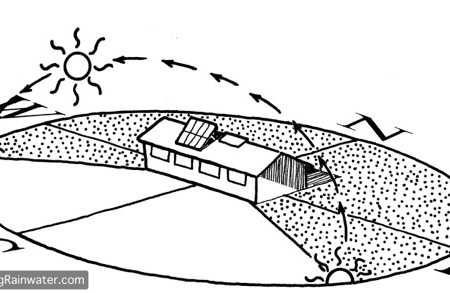

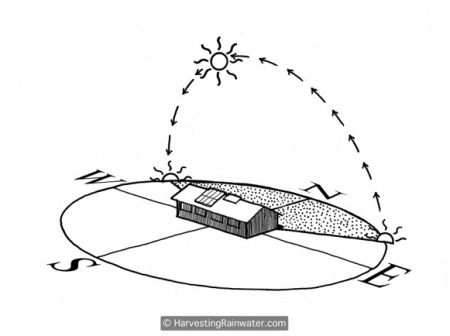

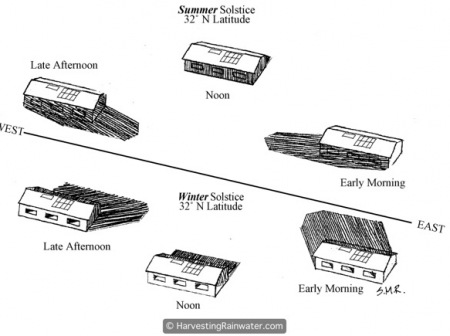

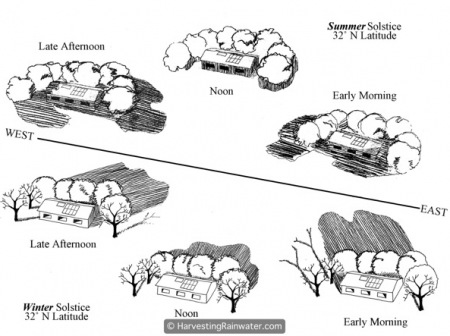

How do the sun’s seasonally changing path and resulting shade affect your home site? How could you work with that sun path to get more free warmth and light in winter, and free shade and cooling in summer? (See figs. 10A & B, below; and chapters 4 and 5, and appendix 7 in Volume 1.)

– Seek out an apartment or workspace with good-to-ideal solar orientation and equator-facing awnings or overhangs (fig. 11, below). See Integrated Design Patterns One and Two in chapter 4 of Volume 1.

– If in a multi-story building, see if you can get an equator-facing balcony &/or windows that give you more free daylight and a warmer microclimate (outside on the balcony &/or inside) during the colder—and darker—seasons.

– Note that an apartment or office unit between east- and west-facing units will likely have lower utility bills, since the neighbors to the east and west will be paying to heat and cool their space and your shared walls.

– If you have access to a yard or adjoining public right-of-way, see if planting a tree(s) within or beside a water-harvesting earthwork could enhance or form a piece of a summer shading solar arc that would not block ideal winter sun access (see fig. 12, below; Integrated Design Patterns Three and Five in chapter 4 of Volume 1). If so, work with the landowner or neighborhood to plant that tree(s) and the rainwater it needs.

– Open all curtains and blinds of equator-/winter-sun-facing windows during sunny winter days, and close them on winter nights.

– Before turning on a heating or cooling system, consider whether outside temperatures could give you that desired heating or cooling for free. If so, open windows instead! Indoor and outdoor thermometers help determine when you want to bring outdoor temperatures inside (fig. 13, below).

– Put up shade sails or shade screens such as exterior window blinds in summer, take ‘em down in winter (fig. 14, below).

– Dry your clothes on a clothesline (solar clothes dryer) or drying rack as opposed to using a mechanical clothes dryer.

– Try using a solar oven—especially in the hot months—to reduce the generation of unwanted heat inside the house.

Wind and Passive Ventilation

From what direction does the wind blow? Does this change during the day, night, or seasons? If so, how? What are the conditions of the wind (hot, cold, dry, wet, strong, weak)? How could you harvest, deflect, or divert that wind for greater comfort and energy savings? (See appendix 8 in Volume 1.)

– Select an apartment or workspace with operable windows and screen doors, ideally with openings to the exterior on at least two different walls of each room to enhance cross-ventilation (and multi-directional daylight) when needed. (See appendix 8 of Volume 1.)

– Look to see if windbreaks planted within or beside water-harvesting earthworks could enhance the passive heating and cooling of your space, while also enhancing your water resources (see appendix 8 of Volume 1).

Enhance Health While Reducing and Utilizing Carbon Emissions and Pollution (in addition to strategies above)

How can you reduce your emission of carbon and pollutants, while enhancing the potential of other life forms that utilize/bioremediate carbon and pollutants as food/nutrients?

– Enhance the growth of carbon eaters and pollution eaters (such as plants and beneficial soil microorganisms). Plant food-bearing shade trees within or beside water-harvesting earthworks in the public right-of-way along public streets. Then, direct street runoff to the earthworks, so the street runoff freely irrigates the street trees, which will grow to shade and cool the street and adjoining footpath. This will make it more desirable to walk or bike than to drive (see figs. 15A & B, below).

Mulch the basin of the earthwork with leaves and cut-up prunings to feed soil microorganisms that will bioremediate contaminants in the street runoff, help sequester carbon in the soil, and enhance the fertility of the soil and health of the trees (fig. 15C).

– Walk and bicycle whenever you can, then look to public transport before driving. The website www.WalkScore.com and the Walk Score app are great for finding apartments, schools, and job sites well-suited to this lifestyle. The resources section at the end of my blog post, Human-Empowered, Enlightened, and Energized Transport, offers lots more bicycling resources.

– Advocate for more walkable and bikeable infrastructure and polices, along with better public transport. See www.LivingStreetsAlliance.org.

– Telecommute or Skype rather than traveling to meet.

– Eat locally raised food (which has not traveled such great distances). Grow some of your own, even if just herbs in pots on your windowsill.

– Eat less meat, and when you do eat meat, opt for locally hunted or grass-fed meat (rather than high- energy- and water-consuming feedlot meat).

– Modify yourself before you turn on an air conditioner or heater. Wear shorts and sandals in summer; wear socks, slippers, long johns, sweaters—and even a hat and scarf—in winter.

– If using a heater or air conditioner, use a single-room device where people most often congregate, instead of using a central heater or air conditioner that heats or cools all the interior spaces (most of which are unoccupied most of the time). The idea here is to heat or cool people rather than empty space.

– Buy renewable green power, and frequent businesses that do the same. Either rent a place with on-site renewable power production, contact your power utility to see if you can purchase renewable power from them (may cost slightly more than their non-renewable power), or invest in a regional community solar or wind project, cooperative, or collective.

– See appendix 9 in Volume 1 for more ideas.

Plants

How many plants can you identify in your area? As with getting to know your human neighbors, the better you get to know you plant neighbors, the more dynamic and engaging you will find your community to be. Potential will increase. Do you know how different cultures and wildlife use these plants? How could you utilize these plants? Are there other climate-appropriate multi-use plants you could incorporate into the system?

– Learn about local wild and cultivated food and medicinal plants from books, local botanical gardens, permaculturalists, naturalists, ethnobotanists, primitive skills enthusiasts, plant walks, and appendix 4. See www.DesertHarvesters.org for videos in English and Spanish on the use of some southwestern-U.S. plants.

Become a Neighborhood Forester

– Try harvesting from and utilizing those plants (fig. 16, below)—after making sure you have identified the plant correctly—ideally with someone already knowledgeable in this area.

– Plant more of these multi-use plants within or beside water-harvesting earthworks—especially where their water needs will be met by on-site water sources (rainwater, stormwater, greywater, air-conditioning condensate) and their shade will meet on-site needs for summer shade, winter sun access, etc (chapter 4 of Volume 1).

– Graft food-bearing stock onto existing ornamental fruit trees (visit Guerrilla Grafters on Facebook).

Community

Exchange makes ecosystems, cultures, and communities vibrant. So how could you better tap into the learning and experience of others, while sharing your evolving understanding of how to live in a more beneficially integrated way with the people and place in which you live? I find learning and exploring more fun with others, and it encourages us to go even further—shared adventure!

– Seek out people and organizations promoting and utilizing strategies you are interested in.

– Organize a party, hike, potluck, skill share, etc., to facilitate juicy exchange. Maybe have a hands-on work-party component that leverages change as you exchange.

– Get involved. Invite and reward involvement.

Over 1,275 food-bearing native trees have been planted by neighborhood volunteers within our neighborhood by since 1996 (many within or beside water-harvesting earthworks). This has dramatically increased beauty, comfort, food-production, flood-control, wildlife habitat, direct connection with the flora and fauna of our local ecosystem, and more. But just as importantly, these plantings helped shift the neighborhood from one of strangers in houses and apartments to a community where more and more people know one another, greet one another, help one another, and work and play together (figs. 17 and 18, below).

This exchange has led to further exchange—such as solar-cooking potlucks; neighbors advocating for each other’s solar rights/access; pie parties; barn-raising-like cistern- and rain-garden-building parties; greywater-harvesting tours, installations, and troubleshooting; the planting of a water-harvesting community orchard; water-harvesting traffic calming in our streets; story-telling public art within and along our streets; parades of bicyclists, walkers, skateboarders, scooters, and dancers; Easter-egg-decorating parties followed by Easter-egg hunts; and more (fig. 19, below). This exchange is what is at the heart of community, and represents much of its true health and wealth (see chapter 5 of Volume 1 for more).

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1